Was White Supremacist Slave Owner and Anti-Abolitionist Lawyer Francis Scott Key a Racist? Is the Song Racist? Is this Song almost impossible to technically sing?

On September 14, 1814, Francis Scott Key penned a poem which is later set to music and in 1931 becomes America’s national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

The poem, originally titled “The Defence of Fort M’Henry,” was written after Key witnessed the Maryland fort being bombarded by the British during the War of 1812. Key was inspired by the sight of a lone U.S. flag still flying over Fort McHenry at daybreak, as reflected in the now-famous words of the “Star-Spangled Banner”: “And the rocket’s red glare, the bombs bursting in air, Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there.”

Francis Scott Key was born on August 1, 1779, at Terra Rubra, his family’s estate in Frederick County (now Carroll County), Maryland. He became a successful lawyer in Maryland and Washington, D.C., and was later appointed U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia.

On June 18, 1812, America declared war on Great Britain after a series of trade disagreements. In August 1814, British troops invaded Washington, D.C., and burned the White House, Capitol Building, and Library of Congress. Their next target was Baltimore.

After one of Key’s friends, Dr. William Beanes was taken prisoner by the British, Key went to Baltimore, located the ship where Beanes was being held, and negotiated his release. However, Key and Beanes weren’t allowed to leave until after the British bombardment of Fort McHenry. Key watched the bombing campaign unfold from aboard a ship located about eight miles away. After a day, the British were unable to destroy the fort and gave up. Key was relieved to see the American flag still flying over Fort McHenry and quickly penned a few lines in tribute to what he had witnessed.

The poem was printed in newspapers and eventually set to the music of a popular English drinking tune called “To Anacreon in Heaven” by composer John Stafford Smith. People began referring to the song as “The Star-Spangled Banner” and in 1916 President Woodrow Wilson announced that it should be played at all official events. It was adopted as the national anthem on March 3, 1931.

Francis Scott Key died of pleurisy on January 11, 1843.

IN-DEPTH: Who Was Francis Scott Key?

Francis Scott Key (August 1, 1779 – January 11, 1843) was an American lawyer, author, and amateur poet from Frederick, Maryland, who is best known for writing the lyrics for the American national anthem “The Star-Spangled Banner”.

Key observed the British bombardment of Fort McHenry in 1814 during the War of 1812. He was inspired upon seeing the American flag still flying over the fort at dawn and wrote the poem “Defence of Fort M’Henry”; it was published within a week with the suggested tune of the popular song “To Anacreon in Heaven”.

The song with Key’s lyrics became known as “The Star-Spangled Banner” and slowly gained popularity as an unofficial anthem, finally achieving official status more than a century later under President Herbert Hoover as the national anthem.

Key was a lawyer in Maryland and Washington D.C. for four decades and worked on important cases, including the Burr conspiracy trial, and he argued numerous times before the Supreme Court. He was nominated for District Attorney for the District of Columbia by President Andrew Jackson, where he served from 1833 to 1841. Key was a devout Episcopalian.

Key owned slaves from 1800, during which time abolitionists ridiculed his words, claiming that America was more like the “Land of the Free and Home of the Oppressed”.

As District Attorney, he suppressed abolitionists, and in 1836 lost a case against Reuben Crandall where he accused the defendant’s abolitionist publications of instigating slaves to rebel. He was also a leader of the American Colonization Society which sent freed slaves to Africa.

He freed some of his slaves in the 1830s, paying one ex-slave as his farm foreman to supervise his other slaves. He publicly criticized slavery and gave free legal representation to some slaves seeking freedom, but he also represented owners of runaway slaves. At the time of his death, he owned eight slaves.

Early Life

Key’s father John Ross Key was a lawyer, a commissioned officer in the Continental Army, and a judge of English descent. His mother Ann Phoebe Dagworthy Charlton was born (February 6, 1756 – 1830), to Arthur Charlton, a tavern keeper, and his wife, Eleanor Harrison of Frederick in the colony of Maryland.

Key grew up on the family plantation Terra Rubra in Frederick County, Maryland (now Carroll County). He graduated from St. John’s College, Annapolis, Maryland, in 1796 and read law under his uncle Philip Barton Key who was loyal to the British Crown during the War of Independence.

He married Mary Tayloe Lloyd on January 1, 1802, daughter of Edward Lloyd IV of Wye House and Elizabeth Tayloe, daughter of John Tayloe II of Mount Airy and sister of John Tayloe III of The Octagon House.

“The Star-Spangled Banner”

During the War of 1812, following the Burning of Washington in August 1814, on September 7, 1814, Key and American Agent for Prisoners of War, Colonel John Stuart Skinner dined aboard HMS Tonnant as the guests of Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane, Rear Admiral George Cockburn, and Major General Robert Ross. Skinner and Key were there to plead for the release of Dr. William Beanes, an elderly resident of Upper Marlboro, Maryland, and a friend of Key, who had been captured in his home on August 28, 1814.

Beanes was accused of aiding the arrest of some British soldiers (stragglers withdrawing after the Washington campaign) who were pillaging homes. Skinner, Key, and the released Beanes were allowed to return to their own truce ship, under guard, but not allowed to leave the fleet because they had become familiar with the strength and position of the British units and their intention to launch an attack upon Baltimore.

Key was unable to do anything but watch the 25-hour bombardment of the American forces at Fort McHenry during the Battle of Baltimore from the dawn of September 13 through the morning of the 14th, 1814.

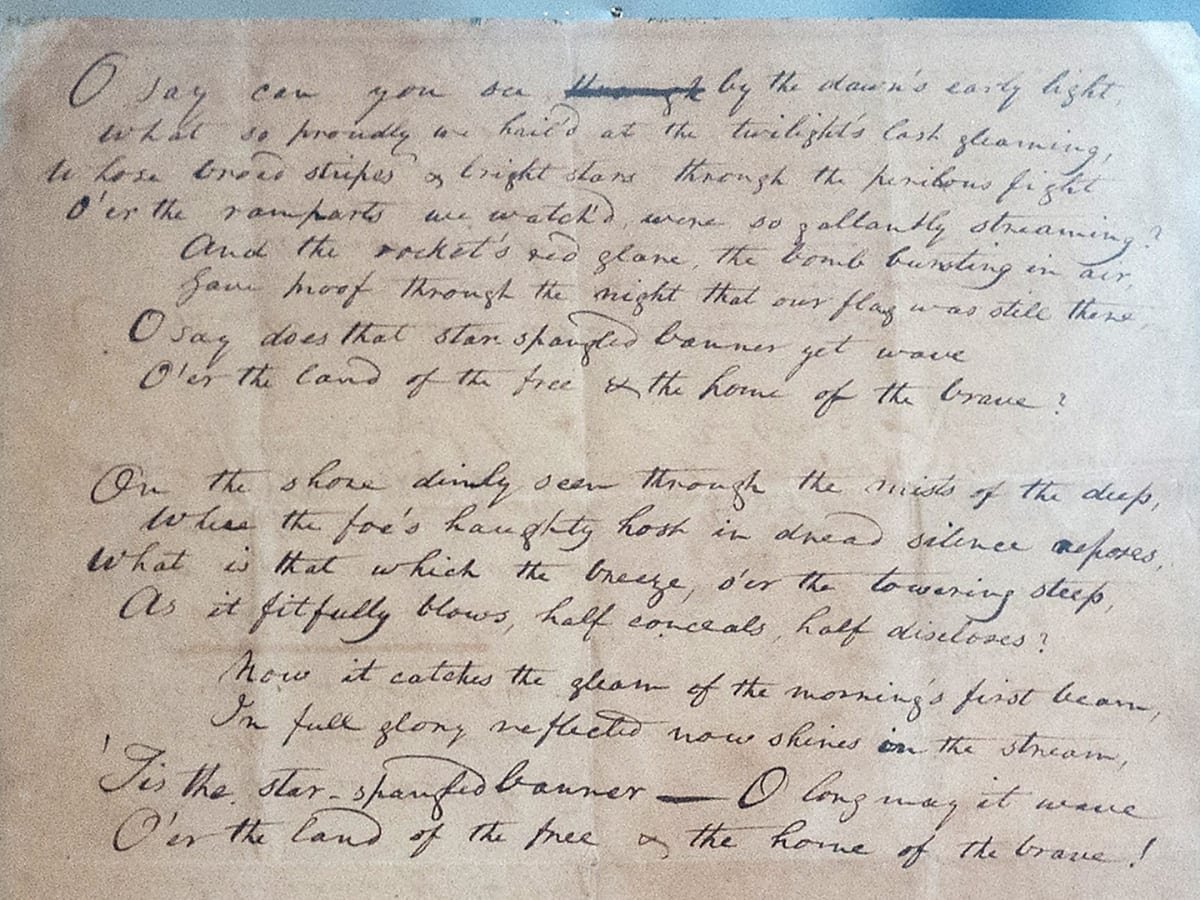

At dawn, Key was able to see a large American flag waving over the fort, and he started writing a poem about his experience, on the back of a letter he had kept in his pocket. On September 16, Key, Skinner, and Beanes were released from the fleet. When they arrived in Baltimore that evening, Key completed the poem at the Indian Queen Hotel, where he was staying, His finished manuscript was untitled and unsigned. When printed as a broadside the next day, it was given the title “Defence of Fort M’Henry” with the notation: “Tune – Anacreon in Heaven”

This was a popular tune that Key had already used as a setting for his 1805 song “When the Warrior Returns”, celebrating American heroes of the First Barbary War. It was soon published in newspapers first in Baltimore and then across the nation, and given the new title The Star-Spangled Banner.

It was somewhat difficult to sing, yet it became increasingly popular, competing with “Hail, Columbia” (1796) as the de facto national anthem by the time of the Mexican–American War and the American Civil War. The song was finally adopted as the American national anthem more than a century after its first publication by an Act of Congress in 1931 signed by President Herbert Hoover.

The third verse of the Star-Spangled Banner makes disparaging mention of blacks and demonstrates Key’s opinion of their seeking freedom at the time by escaping to fight with the British, who promised them freedom from American enslavement.

Legal Career

Key was a leading attorney in Frederick, Maryland, and Washington, D.C., for many years, with an extensive real estate and trial practice. He and his family settled in Georgetown in 1805 or 1806, near the new national capital. He assisted his uncle Philip Barton Key in the sensational conspiracy trial of Aaron Burr and in the expulsion of Senator John Smith of Ohio. He made the first of his many arguments before the United States Supreme Court in 1807. In 1808, he assisted President Thomas Jefferson’s attorney general in United States v. Peters.

In 1829, Key assisted in the prosecution of Tobias Watkins, former U.S. Treasury auditor under President John Quincy Adams, for misappropriating public funds. He also handled the Petticoat affair concerning Secretary of War John Eaton, and he served as the attorney for Sam Houston in 1832 during his trial for assaulting Representative William Stanbery of Ohio.

After years as an adviser to President Jackson, Key was nominated by the President to District Attorney for the District of Columbia in 1833. He served from 1833 to 1841 while also handling his own private legal cases. In 1835, he prosecuted Richard Lawrence for his attempt to assassinate President Jackson at the top steps of the Capitol, the first attempt to kill an American president.

Key and slavery

Key purchased his first slave in 1800 or 1801 and owned six slaves in 1820. He freed seven of his slaves in the 1830s and owned eight slaves when he died. One of his freed slaves continued to work for him for wages as his farm’s foreman, supervising several slaves.

Key also represented several slaves seeking their freedom, as well as several slave-owners seeking the return of their runaway slaves. Key was one of the executors of John Randolph of Roanoke’s will, which freed his 400 slaves, and Key fought to enforce the will for the next decade and to provide the freed slaves with land to support themselves.

Key is known to have publicly criticized slavery’s cruelties, and a newspaper editorial stated that “he often volunteered to defend the downtrodden sons and daughters of Africa.” The editor said that Key “convinced me that slavery was wrong—radically wrong”.

A quote increasingly credited to Key stating that free blacks are “a distinct and inferior race of people, which all experience proves to be the greatest evil that afflicts a community” is erroneous. The quote is taken from an 1838 letter that Key wrote to Reverend Benjamin Tappan of Maine who had sent Key a questionnaire about the attitudes of Southern religious institutions about slavery.

Rather than representing a statement by Key identifying his personal thoughts, the words quoted are offered by Key to describe the attitudes of others who assert that formerly enslaved blacks could not remain in the U.S. as paid laborers.

This was the official policy of the American Colonization Society. Key was an ACS leader and fundraiser for the organization, but he himself did not send the men and women he freed to Africa upon their emancipation. The original confusion around this quote arises from ambiguities in the 1937 biography of Key by Edward S. Delaplaine.

Key was a founding member and active leader of the American Colonization Society (ACS), whose primary goal was to send free blacks to Africa. Though many free blacks were born in the United States by this time, historians argue that upper-class American society, of which Key was a part, could never “envision a multiracial society”. The ACS was not supported by most abolitionists or free blacks of the time, but the organization’s work would eventually lead to the creation of Liberia in 1847.

Anti-abolitionism

In the early 1830s, American thinking on slavery changed quite abruptly. Considerable opposition to the American Colonization Society’s project emerged. Led by newspaper editor and publisher Wm. Lloyd Garrison, a growing portion of the population noted that only a very small number of free blacks were actually moved, and they faced brutal conditions in West Africa, with very high mortality.

Free blacks made it clear that few of them wanted to move, and if they did, it would be to Canada, Mexico, or Central America, not Africa. The leaders of the American Colonization Society, including Key, were predominantly slave owners. The Society was intended to preserve slavery, rather than eliminate it.

In the words of philanthropist Gerrit Smith, it was “quite as much an Anti-Abolition, as Colonization Society”. “This Colonization Society had, by an invisible process, half-conscious, half unconscious, been transformed into a serviceable organ and member of the Slave Power.”

The alternative to the colonization of Africa, the project of the American Colonization Society, was the total and immediate abolition of slavery in the United States. This Key was firmly against, with or without slave owner compensation, and he used his position as District Attorney to attack abolitionists.

In 1833, he secured a grand jury indictment against Benjamin Lundy, editor of the anti-slavery publication Genius of Universal Emancipation, and his printer William Greer, for libel after Lundy published an article that declared, “There is neither mercy nor justice for colored people in this district [of Columbia]”. Lundy’s article, Key said in the indictment, “was intended to injure, oppress, aggrieve, and vilify the good name, fame, credit & reputation of the Magistrates and constables” of Washington. Lundy left town rather than face trial; Greer was acquitted.

Prosecution of Reuben Crandall

In a larger unsuccessful prosecution, in August 1836 Key obtained an indictment against Reuben Crandall, brother of controversial Connecticut teacher Prudence Crandall, who had recently moved to Washington, D.C. It accused Crandall of “seditious libel” after two marshals (who operated as slave catchers in their off hours) found Crandall had a trunk full of anti-slavery publications in his Georgetown residence/office, five days after the Snow riot, caused by rumors that a mentally ill slave had attempted to kill an elderly white woman.

In an April 1837 trial that attracted nationwide attention and that congressmen attended, Key charged that Crandall’s publications instigated slaves to rebel. Crandall’s attorneys acknowledged he opposed slavery but denied any intent or actions to encourage rebellion. Evidence was introduced that the anti-slavery publications were packing materials used by his landlady in shipping his possessions to him. He had not “published” anything; he had given one copy to one man who had asked for it.

Key, in his final address to the jury, said:

Are you willing, gentlemen, to abandon your country, to permit it to be taken from you, and occupied by the abolitionist, according to whose taste it is to associate and amalgamate with the negro? Or, gentlemen, on the other hand, are there laws in this community to defend you from the immediate abolitionist, who would open upon you the floodgates of such extensive wickedness and mischief?

The jury acquitted Crandall of all charges. This public and humiliating defeat, as well as family tragedies in 1835, diminished Key’s political ambition. He resigned as District Attorney in 1840. He remained a staunch proponent of African colonization and a strong critic of the abolition movement until his death.

Crandall died shortly after his acquittal of pneumonia contracted in the Washington jail.

Religion

Key was a devout and prominent Episcopalian. In his youth, he almost became an Episcopal priest rather than a lawyer. Throughout his life, he sprinkled biblical references in his correspondence. He was active in All Saints Parish in Frederick, Maryland, near his family’s home. He also helped found or financially support several parishes in the new national capital, including St. John’s Episcopal Church in Georgetown, Trinity Episcopal Church in present-day Judiciary Square, and Christ Church in Alexandria (at the time, in the District of Columbia).

From 1818 until his death in 1843, Key was associated with the American Bible Society. He successfully opposed an abolitionist resolution presented to that group around 1838.

Key also helped found two Episcopal seminaries, one in Baltimore and the other across the Potomac River in Alexandria (the Virginia Theological Seminary). Key also published a prose work called The Power of Literature, and Its Connection with Religion in 1834.

Death and legacy

On January 11, 1843, Key died at the home of his daughter Elizabeth Howard in Baltimore from pleurisy at age 63. He was initially interred in Old Saint Paul’s Cemetery in the vault of John Eager Howard but in 1866, his body was moved to his family plot in Frederick at Mount Olivet Cemetery.

The Key Monument Association erected a memorial in 1898 and the remains of both Francis Scott Key and his wife, Mary Tayloe Lloyd, were placed in a crypt at the base of the monument.

Despite several efforts to preserve it, the Francis Scott Key residence was ultimately dismantled in 1947. The residence had been located at 3516–18 M Street in Georgetown.

Though Key had written poetry from time to time, often with heavily religious themes, these works were not collected and published until 14 years after his death. Two of his religious poems used as Christian hymns include “Before the Lord We Bow” and “Lord, with Glowing Heart I’d Praise Thee”.

In 1806, Key’s sister, Anne Phoebe Charlton Key, married Roger B. Taney, who would later become Chief Justice of the United States. In 1846 one daughter, Alice, married U.S. Senator George H. Pendleton and another, Ellen Lloyd, married Simon F. Blunt.

In 1859, Key’s son Philip Barton Key II, who also served as United States Attorney for the District of Columbia, was shot and killed by Daniel Sickles—a U.S. Representative from New York who would serve as a general in the American Civil War—after he discovered that Philip Barton Key was having an affair with his wife. Sickles was acquitted in the first use of the temporary insanity defense.

In 1861, Key’s grandson Francis Key Howard was imprisoned in Fort McHenry with the Mayor of Baltimore George William Brown and other locals deemed to be Confederate sympathizers.[citation needed]

Key was a distant cousin and the namesake of F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose full name was Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald. His direct descendants include geneticist Thomas Hunt Morgan, guitarist Dana Key, and American fashion designer and socialite Pauline de Rothschild.

Monuments and memorials

Francis Scott Key Monument as it stood in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco until it was toppled in June 2020. The empty plinth is now surrounded by 350 black steel sculptures that honor 350 Africans kidnapped from Angola and transported across the Atlantic on slave ships.

Francis Scott Key Monument in Baltimore. The monument was defaced in 2017 with the words “Racist Anthem” and covered in red paint.

Two bridges are named in his honor. The first is between the Rosslyn section of Arlington County, Virginia, and Georgetown in Washington, D.C. Key’s Georgetown home, which was dismantled in 1947 (as part of construction for the Whitehurst Freeway), was located on M Street NW, in the area between the Key Bridge and the intersection of M Street and Whitehurst Freeway. The location is illustrated on a sign in Francis Scott Key park.

The other bridge is part of the Baltimore Beltway crossing the outer harbor of Baltimore and is located at the approximate point where the British anchored to shell Fort McHenry.

St. John’s College, Annapolis, from which Key graduated in 1796, has an auditorium named in his honor.

Francis Scott Key was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1970.

He is buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Frederick, the same resting place as that of Thomas Johnson, the first governor of Maryland, and friend Barbara Fritchie, who allegedly waved the American flag out of her home in defiance of Stonewall Jackson’s march through the city during the Civil War.

Sources

An interesting and informative article. I’ll give credit where credit is due. More on the history of the Star Spangled Banner can be found here *https://thedocuments(dot)info/Payload/The%20Military%20and%20Constitution%20Regulated%20Inauguration_%20President%20Trump%20by%20Derek%20Johnson%20v3*

Part of a series @ https://thedocuments(dot)info