“Counterpoint” refers to the technique of combining two or more independent melodic lines (voices) so that they sound simultaneously and interact harmonically, yet each retains its individual identity. In the words of one modern introduction: it’s when “two completely different melodic lines happen at the same time.”

Unlike simple accompaniment (melody + chords), true counterpoint gives each voice more autonomy: each has its own contour, rhythm and melodic interest, but together they combine into a coherent whole.

Historically, composers developed “species counterpoint” (first-species, second-species, etc.) as pedagogical tools to train voice-leading and intervallic independence.

So, in short: when you hear two (or more) good melodies weaving together, not simply harmonizing beneath a main tune, you’re often hearing counterpoint in action.

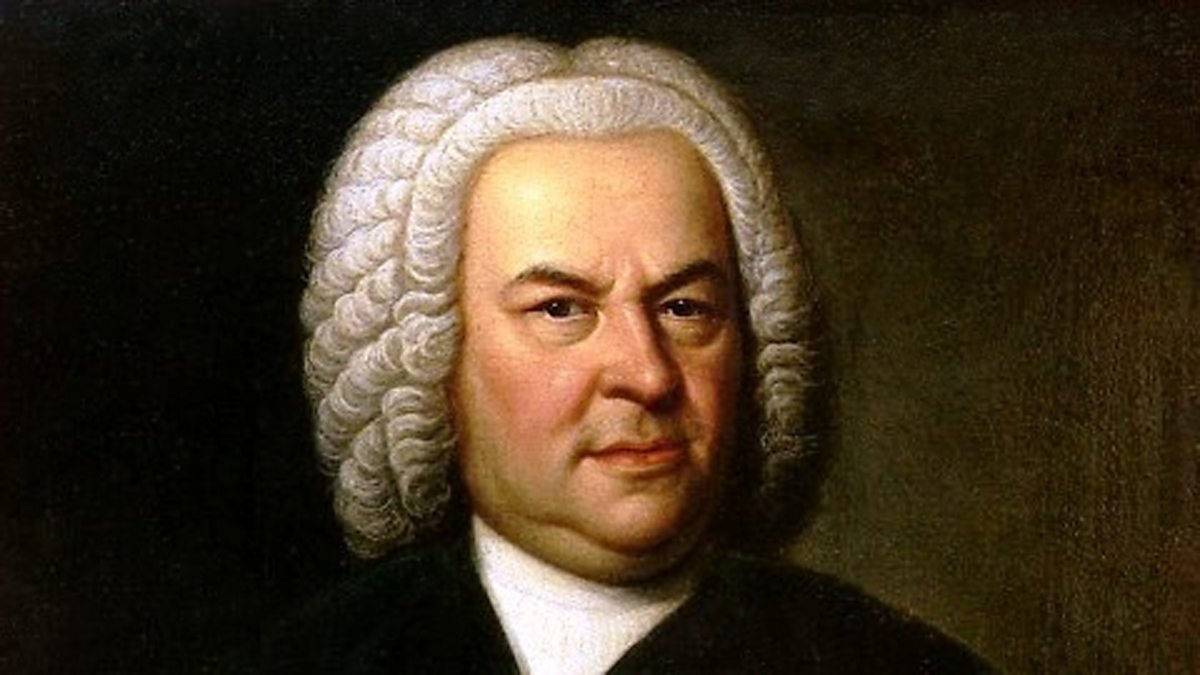

The Father of Counterpoint: Johann Sebastian Bach

While counterpoint existed long before Bach, his mastery and formalization of it in the Baroque era earned him the title “father” (or at least one of the greatest masters) of contrapuntal technique.

For example:

- He used many fugues and canons, where independent voices enter and interact, rather than simply supporting a main melody.

- A source notes: “Bach’s music is full of counterpoint … If you don’t know how to listen to it properly, it can sound like a mess of incomprehensible lines.”

- As one historical overview says: “Johann Sebastian Bach … is renowned for his mastery of counterpoint. His innovative techniques in combining independent voices.”

One could point to his Inventions and Sinfonias, The Well-Tempered Clavier, his many fugues, canons, and chorale preludes — each offering lines that are independent yet part of a larger texture. For example, the Wikipedia article notes: “Bach is revered as one of the greatest masters of counterpoint.”

Why is this important for a composer (such as yourself)? Because the technique of counterpoint offers a way of adding depth, interest and interplay between voices — far beyond simply stacking harmonies under a melody.

How To Use Counterpoint: Key Principles

Before looking at modern examples, here are some practical takeaways for using counterpoint in your music:

- Voice independence: Each melodic line should have its own direction, contour,and rhythm rather than being a mere echo of the main melody.

- Interaction rather than duplication: Voices should respond to each other, perhaps in contrary motion, imitative entrances, or overlapping entries, rather than always moving in lockstep.

- Balance of tension & release: Even though the voices are independent, the overall harmony and interplay should feel intentional — dissonances can be used, but must resolve in a satisfying way.

- Layering textures: In modern music, you can use counterpoint between lead vocals and background vocals, between vocal lines and instrumental riffs, between a bass line and melody, etc. Even if it is less formal than a Baroque fugue, the same spirit holds.

- Spot moments for ‘hook + counter-hook’: Use a strong melodic hook, then overlay a contrasting line (vocal or instrumental) that dovetails with it but retains its own identity.

Modern Examples of Counterpoint in Popular Music

Here are three examples of how counterpoint appears in modern songs — including your own work.

1. Silly Love Songs by Paul McCartney

McCartney’s 1976 hit is a great demonstration of counterpoint in a pop context. The Wikipedia article notes: “The song includes a build-up of multiple vocal parts sung in counterpoint.”

HEAR IT NOW!!!!

Go to 04:13 of the music video above to hear McCartney’s 3-part vocal counterpoint. It’s incredible and super inspiring!

In the song, you can hear:

- A primary melody (Paul’s lead vocal)

- Background vocal parts (Linda McCartney, others) that enter and interact with the lead vocal rather than simply harmonizing in parallel

- Horns and string lines that offer melodic material of their own, weaving in and out of the main vocal line

This makes the texture richer than a standard verse-chorus pop song: the parts overlap, contrast, and interlock.

For your songwriting: study how McCartney uses a strong hook, then layers additional lines that almost become counter-melodies in their own right. Notice how the bass line is also quite independent.

2. Goodnight Irene by Johnny Punish & MarcyElle

Here is how my latest song, a cover of Leadbelly’s “Goodnight Irene, uses counterpoint effectively:

HEAR IT NOW!!!!

Go to 02:15 of the music video above to hear my use of 3-part vocal counterpoint inspired by McCartney. Of course, it’s not as good. But hey, he’s Paul McCartney and I’m not. So there’s that!

- This gives the listener’s ear something extra to track: not just “here is the melody, here are the harmonies”, but “here is a second melodic line weaving in.”

- In effect, you apply the principle: strong melodic hook + contrasting independent line = richer texture and memorable moment.

- By referencing the 80s sax-pop context, the counterpoint becomes part of the arrangement’s new flair (lead vocal, background vocal counterpoint, sax riffs, etc).

So in my songwriting and production, I illustrate how a modern pop/indie song can borrow the spirit of Baroque counterpoint (multiple independent voices) while staying rooted in contemporary genre. I show that counterpoint isn’t just for classical fugues — it’s a tool I use to make “Goodnight Irene” interesting and dynamic.

Why It Matters & How You Can Use It

- Increased listener engagement: When multiple melodies interact, our ear is stimulated by the interplay — we follow one line, then another — and the texture feels more “alive.”

- Distinctive hooks: Instead of relying solely on a catchy hook, you give yourself additional material (a counter‐hook) that supports and elevates the main hook.

- Genre fusion: In your case (80s sax-pop revival), counterpoint offers a way to meld vintage sensibilities (melody + harmony) with modern arrangement (pop duet, sax riffs, etc).

- Arrangement flexibility: You can employ counterpoint in different ways: vocal lines, instrumental lines (sax, guitar), rhythmic patterns, bass vs melody, etc.

- Highlight moments: Choose spots in your song (like the 2:40 mark in “Goodnight Irene”) to open space for a contrapuntal moment — maybe drop the full band, bring in the two voices in free interplay, add a sax counter-melody, etc.

Conclusion

Counterpoint is not a dusty relic of the Baroque era — it remains a vibrant, powerful tool for songwriters, arrangers and producers. From the mastery of J. S. Bach through to Paul McCartney’s pop genius and your own work on “Goodnight Irene”, the idea of independent voices weaving together continues to create rich musical experiences.

By understanding the principles (voice independence, melodic interplay, contrasting lines) and applying them deliberately, you can elevate your songwriting and arrangement. Your song serves as a showcase: you’ve taken inspiration from a classical tool, filtered it through 80s pop, and made it yours.