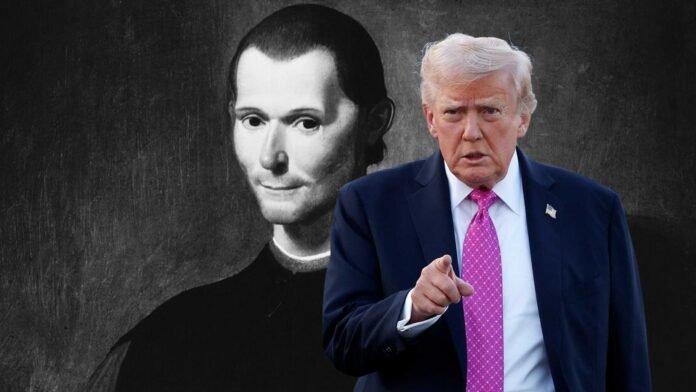

Donald Trump is frequently described as “Machiavellian,” a term meant to suggest cold calculation, strategic genius, and ruthless competence.

The label is convenient, but it is wrong. When we examine Trump’s actual behavior—not his words, branding, or mythology—we find something very different. Trump is not a Machiavellian prince. He is something far less coherent, and far more revealing about the moment America finds itself in.

To understand why this distinction matters, we must first be clear about what Machiavellianism actually is.

What Machiavelli Really Described

In The Prince, Niccolò Machiavelli outlined a model of power that emphasized discipline, restraint, foresight, and institutional durability. A true Machiavellian ruler is willing to be feared rather than loved, but only insofar as fear preserves long-term control. Such a ruler is careful with alliances, manages appearances skillfully, suppresses ego, and avoids unnecessary risks. Above all, Machiavelli prized the stability of power over personal indulgence.

This is where Trump’s behavior diverges sharply.

Trump’s Behavior: Impulse Over Strategy

Trump consistently demonstrates impulsivity rather than strategic patience. He alienates allies, attacks institutions that protect him, and creates crises that offer no long-term advantage. He prioritizes public adoration over quiet consolidation of power, and personal grievance over political sustainability. A Machiavellian leader would never repeatedly expose himself to legal, political, and reputational harm for short-term emotional satisfaction.

Trump does exactly that—again and again.

Where Machiavelli advised rulers to appear virtuous while acting ruthlessly when necessary, Trump often does the opposite: openly indulging in excess, demanding loyalty publicly, and conflating personal identity with the state. This is not cunning. It is exposure.

Power as Ego Reinforcement

Trump’s governing style suggests that power is not an end in itself, but a tool for ego validation. Loyalty matters more than competence. Praise matters more than results. Institutions are valuable only insofar as they serve him personally. When they don’t, they are attacked, delegitimized, or discarded.

This is not Machiavellianism—it is narcissistic instrumentalism. Power exists to reinforce the self, not to preserve the system.

Performative Populism, Not Ideology

Trump is often framed as a populist, but even this description is incomplete. His populism is performative rather than philosophical. There is no consistent worldview, no coherent moral or political framework guiding his actions. “The people” function primarily as an audience and a shield, not as a constituency whose interests are systematically advanced.

Populism, in Trump’s case, is a tactic—not a belief.

Short-Term Wins Over Durable Rule

Perhaps the clearest evidence that Trump is not Machiavellian is his disregard for durability. Machiavelli warned against recklessness and counseled rulers to avoid being hated by the populace at large. Trump routinely embraces division, inflames resentment, and frames governance as a zero-sum contest of humiliation and dominance.

He chooses the immediate “win”—a headline, a rally reaction, a perceived slight avenged—over the slow work of maintaining legitimacy. That is the opposite of strategic rule.

Why the Mislabeling Matters

Calling Trump “Machiavellian” flatters him by implying intelligence, foresight, and mastery of power. It also misleads the public into believing his behavior is part of some grand design. In reality, his conduct suggests something more chaotic and, arguably, more dangerous: a leader unrestrained by philosophy, discipline, or institutional loyalty.

Trump is not executing a plan. He is reacting—to praise, to criticism, to grievance, to ego injury.

A More Accurate Description

If we must name Trump’s governing philosophy based on behavior alone, it is best described as:

Ego-driven opportunism masquerading as strength

Or more plainly:

Governance as personal theater

This matters because systems can defend themselves against strategic adversaries. They struggle far more against leaders who treat power as a mirror rather than a responsibility.

Final Thought

Machiavelli understood something essential: power that is not disciplined destroys itself. Trump’s record suggests not the cunning of The Prince, but the volatility of a man who confuses attention with authority and loyalty with legitimacy.

And perhaps the most unsettling conclusion is this:

Trump’s rise says less about Machiavelli—and far more about what modern America is willing to tolerate, excuse, and ultimately reward.